The incredible history of China’s terracotta warriors

What happens after death? Is there a restful paradise? An eternal torment? A rebirth? Or maybe just nothingness? Well, one Chinese emperor thought that whatever the hereafter was, he better bring an army. We know that because in 1974, farmers digging a well near their small village stumbled upon one of the most important finds in archeological history: vast underground chambers surrounding that emperor’s tomb, and containing more than 8,000 life-size clay soldiers ready for battle.

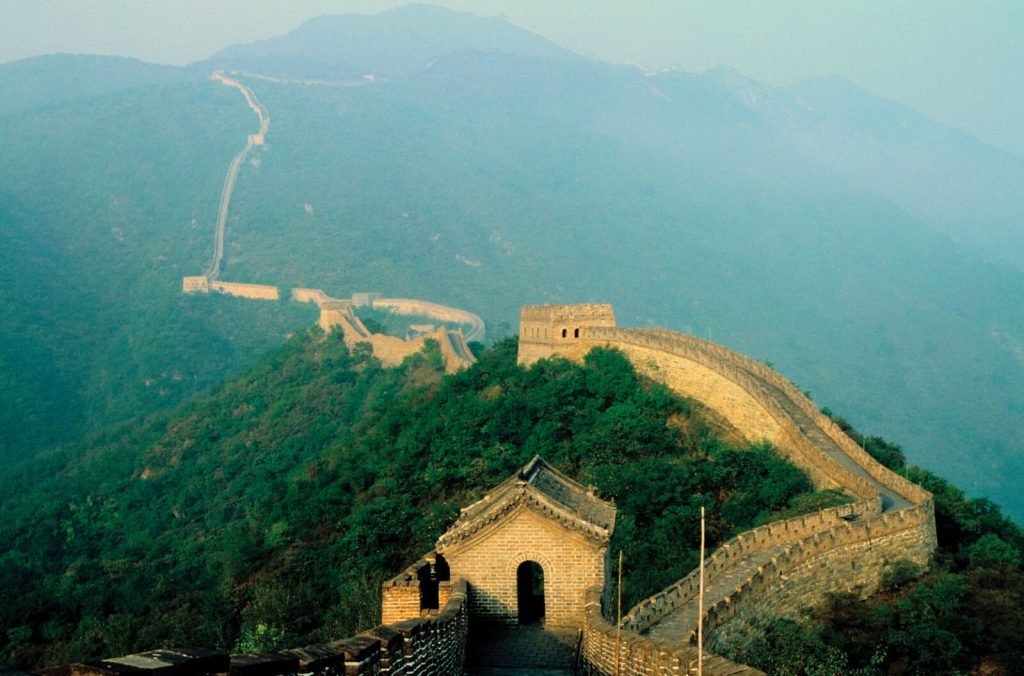

The story of the subterranean army begins with Ying Zheng, who came to power as the king of the Qin state at the age of 13 in 246 BCE. Ambitious and ruthless, he would go on to become Qin Shi Huangdi, the first emperor of China after uniting its seven warring kingdoms. His 36 year reign saw many historic accomplishments, including a universal system of weights and measures, a single standardized writing script for all of China, and a defensive barrier that would later come to be known as the Great Wall.

But perhaps Qin Shi Huangdi dedicated so much effort to securing his historical legacy because he was obsessed with his mortality. He spent his last years desperately employing alchemists and deploying expeditions in search of elixirs of life that would help him achieve immortality. And as early as the first year of his reign, he began the construction of a massive underground necropolis filled with monuments, artifacts, and an army to accompany him into the next world and continue his rule.

This magnificent army is still standing in precise battle formation and is split across several pits. One contains a main force of 6,000 soldiers, each weighing several hundred pounds, a second has more than 130 war chariots and over 600 horses, and a third houses the high command. An empty fourth pit suggests that the grand project could not be finished before the emperor’s death. In addition, nearby chambers contain figures of musicians and acrobats, workers and government officials, and various exotic animals, indicating that Emperor Qin had more plans for the afterlife than simply waging war.

All the figurines are sculpted from terracotta, or baked earth, a type of reddish brown clay. To construct them, multiple workshops and reportedly over 720,000 laborers were commandeered by the emperor, including groups of artisans who molded each body part separately to construct statues as individual as the real warriors in the emperor’s army. They stand according to rank and feature different weapons and uniforms, distinct hairstyles and expressions, and even unique ears. Originally, each warrior was painted in bright colors, but their exposure to air caused the paint to dry and flake, leaving only the terracotta base. It is for this very reason that another chamber less than a mile away has not been excavated.

This is the actual tomb of Qin Shi Huangdi, reported to contain palaces, precious stones and artifacts, and even rivers of mercury flowing through mountains of bronze. But until a way can be found to expose it without damaging the treasures inside, the tomb remains sealed. Emperor Qin was not alone in wanting company for his final destination. Ancient Egyptian tombs contain clay models representing the ideal afterlife, the dead of Japan’s Kofun period were buried with sculptures of horses and houses, and the graves of the Jaina island off the Mexican coast are full of ceramic figurines.

Fortunately, as ruthless as he was, Emperor Qin chose to have servants and soldiers built for this purpose, rather than sacrificing living ones to accompany him, as had been practiced in Egypt, West Africa, Anatolia, parts of North America and even China during the previous Shang and Zhou dynasties. And today, people travel from all over the world to see these stoic soldiers silently awaiting their battle orders for centuries to come.

Responses