How people rationalize fraud

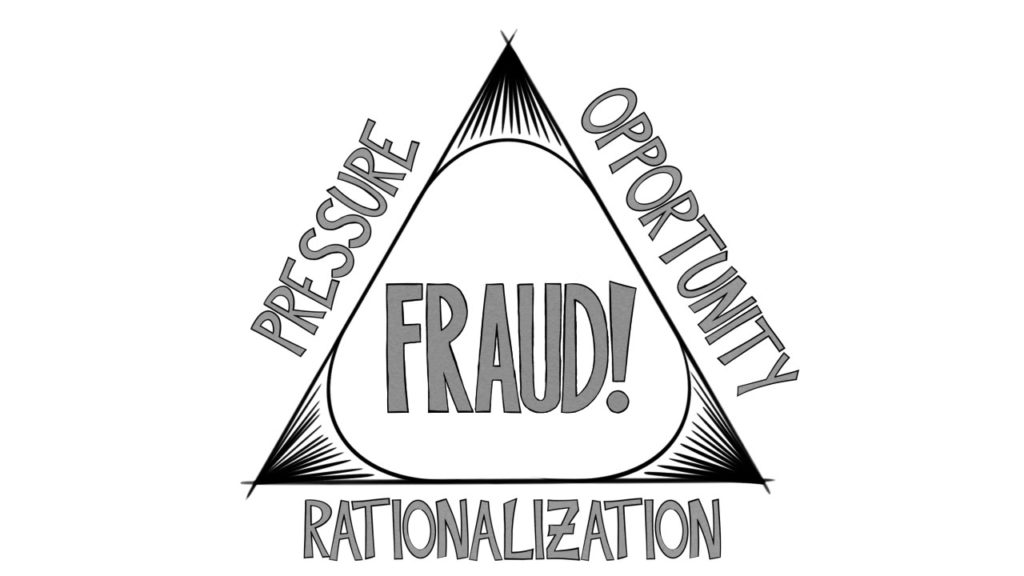

If you ask people whether they think stealing is wrong, most of them would answer, “Yes.” And yet, in 2013, organizations all over the world lost an estimated total of 3.7 trillion dollars to fraud, which includes crimes like embezzlement, pyramid schemes, and false insurance claims. This wasn’t just the work of a few bad apples. The truth is that many people are susceptible not only to the temptation to commit fraud but to convincing themselves that they’ve done nothing wrong. So why does fraud happen? While individual motivations may differ from case to case, the fraud triangle, a model developed by criminologist Donald Cressey, shows three conditions that make fraud likely: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization.

Pressure is often what motivates someone to engage in fraud to begin with. It could be a personal debt, an addiction, an earnings quota, a sudden job loss, or an illness in the family. As for opportunity, many people in both public and private sectors have access to tools that enable them to commit and conceal fraud: corporate credit cards, internal company data, or control over the budget. The combination of pressure and being exposed to such opportunities on a daily basis can create a strong temptation. But even with these two elements, most fraud still requires rationalization. Many fraudsters are first time offenders, so in order to commit an act most would regard as wrong, they need to justify it to themselves. Some feel entitled to the money because they are underpaid and overworked and others believe their fraud is victimless, perhaps even planning to return the money once their crisis is resolved.

Some of the most common types of fraud don’t even register as such to the perpetrator. Examples include employees fudging time sheets or expense reports, taxpayers failing to report cash earnings, or service providers overbilling insurance companies. Though these may seem small, and can sometimes only involve hundreds of dollars, they all contribute to the big picture. And then there’s fraud on a massive scale. In 2003, Italian dairy food giant Parmalat went bankrupt after it was found to have fabricated a 4 billion dollar bank account and falsified financial statements to hide the fact that its subsidiaries had been losing money.

Because it was family controlled, corporate governance and regulator supervision were difficult, and the company likely hoped that the losses could be recouped before anyone found out. And it’s not just corporate greed. Governments and non-profits are also susceptible to fraud. During her time as City Comptroller for Dixon, Illinois, Rita Crundwell embezzled over 53 million dollars. Rita was one of the country’s leading quarter horse breeders and winner of 52 world championships.

But the cost of maintaining the herd ran to 200,000 dollars per month. Because her position gave her complete control over city finances, she was easily able to divert money to an account she used for private expenses, and the scheme went unnoticed for 20 years. It is believed that Crundwell felt entitled to a lavish lifestyle based on her position, and the notoriety her winnings brought to the city. It’s tempting to think of fraud as a victimless crime because corporations and civic institutions aren’t people.

But fraud harms real people in virtually every case: the employees of Parmalat who lost their jobs, the citizens of Dixon whose taxes subsidized horse breeding, the customers of companies which raise their prices to offset losses. Sometimes the effects are obvious and devestating, like when Bernie Madoff caused thousands of people to lose their life savings. But often they’re subtle and not easy to untangle. Yet someone, somewhere is left holding the bill.

Responses